Measuring Costs and Calculating Profits

Some of the easiest questions to ask about your seller account—yet the hardest to answer—have to do with whether you are running a profitable business.

Which products and brands are profitable to you? Which ones should you restock? Which products come with the highest opportunity cost if you run out of stock?

In this chapter, we discuss the importance of understanding your profitability so you can make smart decisions about inventory management, procurement, and pricing.

Through our combined experience, we have seen too many sellers believe that:

- As topline sales grow, the bottom-line profits are also growing

- As long as they sell for some fixed markup over what they paid, they are making money

- High-volume products typically generate a lot of profit

- Competitors must know what they’re doing, so they should use competitors’ prices as a starting point for their own pricing

- It’s reasonable to evaluate total profits only at year-end when preparing for taxes

We want to equip you with the necessary tools so you can see through all of these costly myths, and build a profitable business by understanding which parts of your business are more profitable than others. Only then can you make intelligent decisions about:

- Which products to replenish vs. which ones to sell through and never replenish again

- Which suppliers, brands, products to pursue

- Which suppliers, brands, products to target for negotiating lower acquisition costs and lower prices

- How to price your products appropriately

- Whether to carry specific products for reasons beyond profit margin

No matter what sort of Amazon seller you are, you most like have the goal of making profits for your business. We will provide guidance and tools on how to track costs—both obvious and hidden costs—so you can make informed decisions about the products you carry in your Amazon catalog.

Throughout this discussion, keep in mind that your objective is to improve your bottom-line profits, while Amazon’s objective is to get you to increase your top-line sales.

You see, Amazon isn’t focused on whether you are making profits on your sale. It wants you to keep selling more and more products, even if you’re doing so unprofitably.

During my tenure at Amazon, we never once rolled out a program focused on helping sellers to improve their profitability and long-term survival – and if a seller ends up imploding through too many losses, Amazon’s approach is to backfill that selection as quickly as possible from as many sellers as possible, again regardless of who is or isn’t making profits doing so. Most of the reports in Seller Central are focused on your topline sales. But we will show you how to pull out information about other costs that are less transparent in the Seller Central reports. Through this data-driven approach, you can make much better decisions that will improve the likelihood that you are working hard to put profits into your own pocket as a first priority.

Terminology

Let’s define a few terms to make sure we are using terminology the same way:

Seller Profits

We use an accounting version of this term: profit (or net income) is the difference between your purchase price and the costs of bringing to market. While sellers usually know the purchase price of their products, there are all sorts of hidden or less apparent costs that must be factored into “bringing to market” these products, including overhead costs, opaque Amazon fees, and return-related costs. As we will see in this chapter, these less-apparent costs can add up quickly and result in sellers working very hard to sell products that make Amazon referral fee revenue, but make the sellers no profits or result in a loss.

Opportunity Cost

You have limited time and financial resources. If you weren’t spending your time and capital on the items you sell today, how else could you be using these resources? What interests us most for this discussion is what choices you are making regarding the products you carry in inventory, the quantities of product you carry, and the times of year at which you carry those products. Are you missing out on opportunities for larger profits because of sub-optimal choices you are making today? That is the key question to address here.

Overhead Costs

It costs money to keep your warehouse going, pay your employees, and cover heating, insurance, taxes, licensing, product development, business travel, loan interest, software, and so on. All of these costs are necessary for your business, and have to be included in your evaluation of total costs incurred by your business of being an Amazon seller.

Acquisition Cost

While many sellers often consider this to be the purchase price of products you buy, you may also have inbound shipping costs from your supplier to your facility, bank wiring fees, customs fees, and any other costs directly related to the acquisition of specific products. Our task today is making sure that you are as explicit about as many costs as possible so that as you incur costs, you realize their effect on your overall Amazon seller business, both in aggregate and across each of your products individually.

Repricing Software/Repricers

There are a number of external software providers that offer you automated tools for repricing your offers on Amazon. Typically, you put in a floor price you are prepared to accept, as well as rules for establishing how and when your prices are changed by the software. Unfortunately, too many sellers have embraced this software for its ease of use without first conducting a comprehensive measurement of their total costs, resulting in sellers regularly setting floor prices that put them underwater without their realizing it. These software packages can be helpful at automating an otherwise laborious repricing task, but should only be used when the seller is extremely well informed about their total costs.

Data-Driven Purchasing: Profitability/Cost Measurement

Our philosophy on managing costs in a successful Amazon seller business consists of three main tenets.

1. Be Inclusive on Costs

Inclusion: Identify and allocate as many costs as possible. If you are incurring costs, you want to make sure you can include those costs in your model Even if you put the cost in exactly the right place, it’s more important to make sure you bring to light the cost in the first place.

2. The SKU is the First Level of Analysis

The SKU is the first level of analysis. You need to build a model that allows you to allocate costs down to the SKU level.

While some costs will have to be averaged and applied across all SKUs, some costs can be assigned to specific SKUs.

Either way, the key point here is look at your business at granular level rather than an overall level.

Understanding profitability at a SKU level and at a brand level provide necessary insight for success. While you can always roll up from the SKU-level view to the whole business, if you don’t collect and allocate data to the SKU level, you won’t gain the critical insight on which SKUs are most profitable or least profitable to your business.

Only at the SKU and brand levels can you take specific actions to correct inventory, procurement, and pricing practices.

3. Conduct Regular, Repeated Measurement

Regular, repeated measurement: Profitability should be tracked throughout the year, not just at the end of the year.

If you have SKUs that are hemorrhaging profits, you want to know as soon as possible so you can take corrective actions.

Likewise, if you have highly profitable products, you want to know that so you can take preemptive actions to prevent stock-outs.

While it may not be practical to update your profitability measurements daily or weekly, we encourage you to update your data at least monthly in order to identify any changing trends or newly problematic parts of your business.

Cost Tracking

So where are these costs that we need to track to get a clean view of your actual margins?

We break these into transactional and overhead costs:

Transactional Costs

Transactional costs include:

- Cost of Goods Sold

- Shipping costs from your supplier to you

- Shipping costs from you to FBA

- FBA shipping costs

- Shipping costs to customer

- Referral fee paid to Amazon

- Per item fee paid to Amazon

- Customs and wiring fees

- Product return costs and fees

Overhead Costs

Overhead costs include:

- Monthly Amazon fee

- Warehouse costs (insurance, rent, labor, utilities, repairs, office expenses, property tax, storage, etc.)

- Cost for product samples

- Travel costs, membership dues, certification fees, legal fees, licensing, health care expenses

- FBA storage fees (short-term and long-term)

- FBA Inventory Placement Service Fee

- Shortage

- Computing and web expenses

- Feedback Software

- Re-pricing Software

- Channel Management/ Inventory Management Software

- Additional Marketplace Software

- Any other miscellaneous business expenses

- Inventory Financing costs

- Amazon state sales service fees

- Uncollected state sales taxes

The first two costs should be well known to sellers, as they buy products from their suppliers.

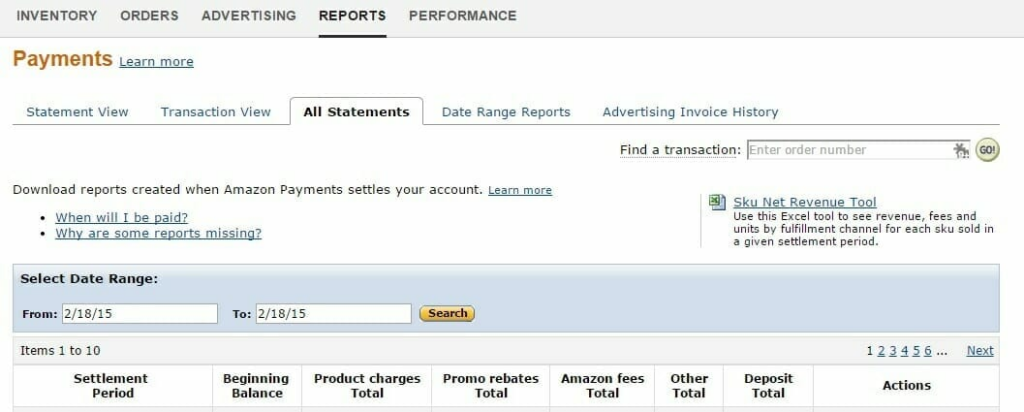

Costs three through eight are all available in the “All Statements” report found under “Reports” -> “Payments” -> “All Statements”:

If the sellers are buying product from overseas, the customs and bank wiring fees are also usually reasonably accessible, as the customs clearing organization and bank will have records of these items that they share with the seller.

Other Costs and Fees

Now to the harder stuff. While Amazon does report product return costs and fees, most sellers don’t understand them or know how to find and align them with specific SKUs.

Return Rates

Not all products have the same likelihood of being returned by customers. Furthermore, FBA products usually have a higher return rate than products fulfilled by the sellers (though FBA products also usually have a high customer conversion rate, which has to be considered in balancing the net impact of FBA on your business). Figuring out the SKU-level return rates in Sellercentral is very confusing – you can see which orders got returned, and you have to apply some tricky footwork to figure out which SKUs in which orders were returned, should the order have been for more than 1 SKU or more than 1 unit of 1 SKU. If the returns are coming directly to you from customers, it’s a lot easier to keep track of what’s been returned than if the product was returned through FBA, where sometimes the product gets returned to Amazon’s FBA returns facility where it is graded by Amazon and returned immediately to your active FBA inventory as re-sellable, while at other times, it is placed in unfulfillable inventory where you will need to either pull it back to your location, or ask Amazon to dispose of it outright. We will talk more about this in the Order Fulfillment / Returns chapter discussion.

Shipping Costs

When FBA orders are returned by customers, they can get handled in different ways – on some returns, the customer may pay for return shipping, while on others you, the seller, pays for return shipping. And on orders that you fulfill yourself to customers, each seller may have different policies about who pays shipping on returned items.

What To Do With Returned Product

Once the product is returned by the customer, some products are disposed vs. others are cleaned up and prepared for resale.

Resale Rate

The recovery rate on resold items will differ by SKU….on some returned products, it’s easier to resell the item as a new item (still in original packaging, and wasn’t damaged by the original customer) whereas some items can only be sold as used because the original packaging is gone and unreplaceable, or the item has been scuffed, damaged or altered by the customer.

To help with resale of returned products, save all extra parts, packaging, warranty slips, instruction manuals. You may need them to upgrade a returned item back to new condition.

Costs 10-19

- Monthly Amazon fee

- Warehouse costs (insurance, rent, labor, utilities, repairs, office expenses, property tax, storage, etc.)

- Cost for product samples

- Travel costs, membership dues, certification fees, legal fees, licensing, health care expenses

- FBA storage fees (short-term and long-term)

- FBA Inventory Placement Service Fee

- Shortage

- Computing and web expenses

- Feedback Software

- Re-pricing Software

- Channel Management/ Inventory Management Software

- Additional Marketplace Software

- Any other miscellaneous business expenses

- Inventory Financing costs

The issue usually isn’t adding up these costs, but rather figuring out what sort of “overhead” allocation should be applied to your orders (insurance, rent, labor, utilities, repairs, office expenses, property tax, storage, etc.).

Because you have to pay for your overhead costs one way or the other, why not allocate the appropriate portion across your orders so you can factor in this real cost?

Depending on whether you are selling products on other marketplaces or your own website, or using part your warehouse for purposes other than selling products online, you may have to make some adjustments for what portion of each overhead cost you decide to apply to your Amazon business.

And yes, as your business grows, you will likely have to change your overhead cost allocation because hopefully you are able to streamline your business, and require less total overhead per order as you grow your business. We don’t want you to drive yourself crazy calculating and re-calculating overhead cost allocations every month or quarter, but it is worth having some periodically-updated rule of thumb that you can apply to your orders in order to know what is the impact of overhead on your Amazon seller business.

Amazon State Tax Service Fee

Amazon charges 2.9% of the sales tax revenue that it collects for a seller. Hence, a seller will be 2.9% short on the amount of sales tax revenue it gets from Amazon, and the seller will have to cover this difference itself. You can find this “Sales Tax Service Fee” in the “Reports”, “Payments”, “All Statements” files under the “Item-Related-Type-Fee” column.

Uncollected State Sales Taxes

If for some reason, you aren’t collecting sales tax that you do in fact owe on orders you sold, this liability now becomes part of your cost of doing business, and as such, should be considered an expense to be allocated back to your orders.

If you chose to start collecting this, you could eliminate this almost all of out-of-pocket expense (except the Amazon Sales Tax Service Fee).

While you may be not collecting sales tax on some Amazon SKUs while collecting on others, it’s going to be easier just to allocate such a liability across all orders…though if you have found a more appropriate way to allocate to specific SKUs, by all means be our guest!

Keep in mind that some of your Amazon competitors will be small, at-home businesses with nominal overhead, while other Amazon competitors may be part of large multinational companies that have lots of overhead to share with the online sales division.

By measuring and tracking your overhead costs, you can actively work on identifying ways to keep allocated overhead costs as low as possible in order to keep your true total costs in line with the prices at which you charge for online products. A good rule of thumb to consider is that a home-business seller with no warehouse will likely have an overhead allocation cost of under $1.50/unit sold, whereas a company with a warehouse and staff might well have overall costs of $1.00 – $3.00/unit sold. If your profit margin calculations based only on direct product costs are less than $3, you might well be losing money once your overhead allocation costs are applied, leading us to wonder why you aren’t focused instead on:

Lowering Your Overall Overhead Costs & Finding Higher Price-Point Products To Sell

There are two important questions you need to ask when tracking your overhead costs:

- What proportion of each overhead expense should be allocated to your Amazon.com business?

- What overhead cost allocation per unit sold should be made to each of your Amazon.com orders?

What we have found is most sellers do not fully factor in their overhead costs into the margin analysis of their products on Amazon. And hence, many products that might appear to be profitable are not at all profitable once you factor in the overhead cost allocation.

There are several software options out there that allow you to determine if your products are actually profitable or not:

Once you build a profitability model that includes your numbers for all of your different costs, you can figure out how much margin you’ve actually made across all of the units you’ve sold over the past 6-12 months. Once you apply your margin per SKU calculations to each sale, you end up with two useful columns of data:

- % of Revenue generated per SKU

- % of Margin generated per SKU

With this much more comprehensive view of your overall costs, you will uncover the following scenarios:

- You would make more overall profit if you stopped selling certain items

- You would make more overall profit if you focused on never running out of stock on a small portion of products

- You would make more overall profit if you stopped selling low-priced products, and moved that capacity to higher-priced products even if the profit margin on the higher-priced products was less.

Sometimes you may sell a product as long as it generates SOME positive profit. This is a good time to ask if there are other products that generate more positive profit per sale that could replace the inventory investment that you’ve made on these low-margin products.

Repricing Tools

There are a number of “repricing” tools that will help automate how you adjust the pricing of your Amazon listings. Through these tools, the software will, as needed, lower your current price to keep you in a position to win the Buy Box, until the price hits a floor that you have set.

These tools include:

- Appeagle.com

- Teikametrics.com

- Wiser.com

- Channelmax.net

- Feedvisor.com

- Repriceit.com

- BQool.com

- Sellerengine.com/sellery

While the popularity of repricing tools increases among Amazon sellers, we should point out that without a very clear understanding of your all-in costs, it’s quite easy to set your floor price below your breakeven cost, allowing you to price products at a loss unbeknownst to you. We have seen unfortunately too many sellers offering products for sale on Amazon without appropriate consideration of less-visible costs like the overhead costs and return-related costs.

With that in mind, let’s look at different layers of understanding that might be applied to setting a floor price in a repricing tool.

We’ll use the example of wholesaling a SKU for $50 (including shipping to you from your supplier) to be sold at $80 on Amazon, where you will fulfill the item through FBA.

For the purpose of this example, let’s estimate your Amazon referral fee (or commission rate) at 15%:

Initially, looking just at direct product costs, we calculate a profit of:

$80 – 15%*$80 ($12 for referral fee) – ~$3 (for FBA fee) – $50 (acquisition cost) = $15 per unit sold.

If we include the overhead cost allocation of $3/unit, that $15 profit falls to $12.

Let’s say this item is returned 25% of the time by customers, and you are able to resell returned items at 75% of the original new condition price.

The recovery rate of 75% works out to a reduction of $20 on the selling price, which averages out to another $5 cost per item, adjusting for the 25% return rate.

Now keep in mind Amazon will retain 20% of the original referral fee on any item that a customer returns.

So, the $2.40 of Amazon return referral fee per returned item works out to $0.60 per item, returned or not.

If return shipping from the customer to you also costs you $4 per return, we have to account for an average of $1.00 for return shipping across all units, adjusting for the 25% return rate.

And we still haven’t factored in any costs tied to in-bound shipping to FBA, or FBA storage.

Already, that apparent $12 profit per unit sold has dropped by roughly $6.60 ($1 + $0.60 + $5), which equates to a meaningful portion of your initial profit figure of $12.

If you are going to use a repricing tool, make sure you have a very clear understanding of all of your costs, even if you have to use rules of thumb to estimate and allocate those costs.

While we like the idea of automating a task like repricing, it’s crucial that you know all of your costs and incorporate them into your calculation of the lowest price at which you are prepared to sell each SKU.

Furthermore, while you may have a good understanding of those costs, you should be periodically updating them—starting with your overhead allocation costs (typically the biggest ignored cost).

By regularly updating your understanding of your costs, you remain informed about how to price each of your products in a profitable manner.

Processes to Implement

Calculating your profitability is all about keeping track of revenue and cost numbers:

Product Costs

With lots of paperwork and emails coming in from suppliers, we encourage you to organize and document your product acquisition data—whether through purchase orders or packing slips from your suppliers.

While you may be putting some of this information into your accounting software, make sure that you can access your product cost data quickly if you needed to identify acquisition cost per SKU in your Amazon catalog.

Supplier Shipping Costs

If your suppliers charge you separately for shipping, keep track of your total shipping costs per brand per supplier.

It’s usually easiest to document this information when you place an order and get the shipping or billing confirmation from your supplier. So even if you have a simple spreadsheet that shows each order, the number of SKUs by brand in the order, and the total cost of shipping on that order, you will be accumulating the necessary data to make easier calculation of shipping cost per unit of each brand you carry.

We recognize that there may be a lot of averaging of costs here, by way of applying the same shipping cost per unit of the same brand, even if the units vary widely on weight or shipping dimensions. While you can make some adjustments to address some of that variability, we’ve found that it’s not worth the minutiae of de-averaging shipping costs per unit within a brand, as there are usually more important drivers of overall cost to address.

Nonetheless, we want the shipping costs to be included in your profitability model, so we encourage you to update your spreadsheet regularly, rather than having to go back through a huge accumulated pile of invoices or shipping forms to figure out shipping cost per unit per brand.

Overhead Costs

Your overhead costs should be visible in your checkbook, as you’re likely cutting checks each month to pay for most of them. You should be able to pull data from your accounting software or whatever record-keeping process you use to calculate a total overhead cost that needs to be allocated to your Amazon orders.